How to be a fashion activist in 2021 (beyond another slogan t-shirt)

12/4/2021

Fashion has always been political. From the coded colours of the Suffragettes to the unifying monochrome of the Black Panther Party, clothing has long been used as a tool of empowerment, a visual driver of change, or a way to speak when nobody will listen.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that when the world turned upside-down last year, one of the first things people thought to do was wear our hearts on our sleeves – or emblazoned across our chests. Rainbows, NHS logos, ‘I stayed home 2020’; if we were feeling it, chances are someone was selling it on a t-shirt.

The slogan tee has been on a long journey since 1984, when designer Katharine Hamnett famously shook the hand of Margaret Thatcher wearing a t-shirt dress that read ‘58% DON’T WANT PERSHING’, a reference to the Prime Minister’s plans for a nuclear missile base. Whether it’s her iconic ‘CHOOSE LIFE’ tees as worn by Wham!, the ‘STOP WAR, BLAIR OUT’ message she sent down the catwalk in response to the Iraq invasion, or the countless designers and campaigners who have turned a plain tee into a placard in the years since, there’s no denying it can sometimes be a powerful tool of protest.

But not always. As Hamnett herself once put it: “a successful t-shirt has to make you think but then, crucially, you have to act.” In our snap-happy, increasingly optic-driven culture, all too often we’re forgoing the ‘been there, done that’ and skipping straight to ‘got the t-shirt.’

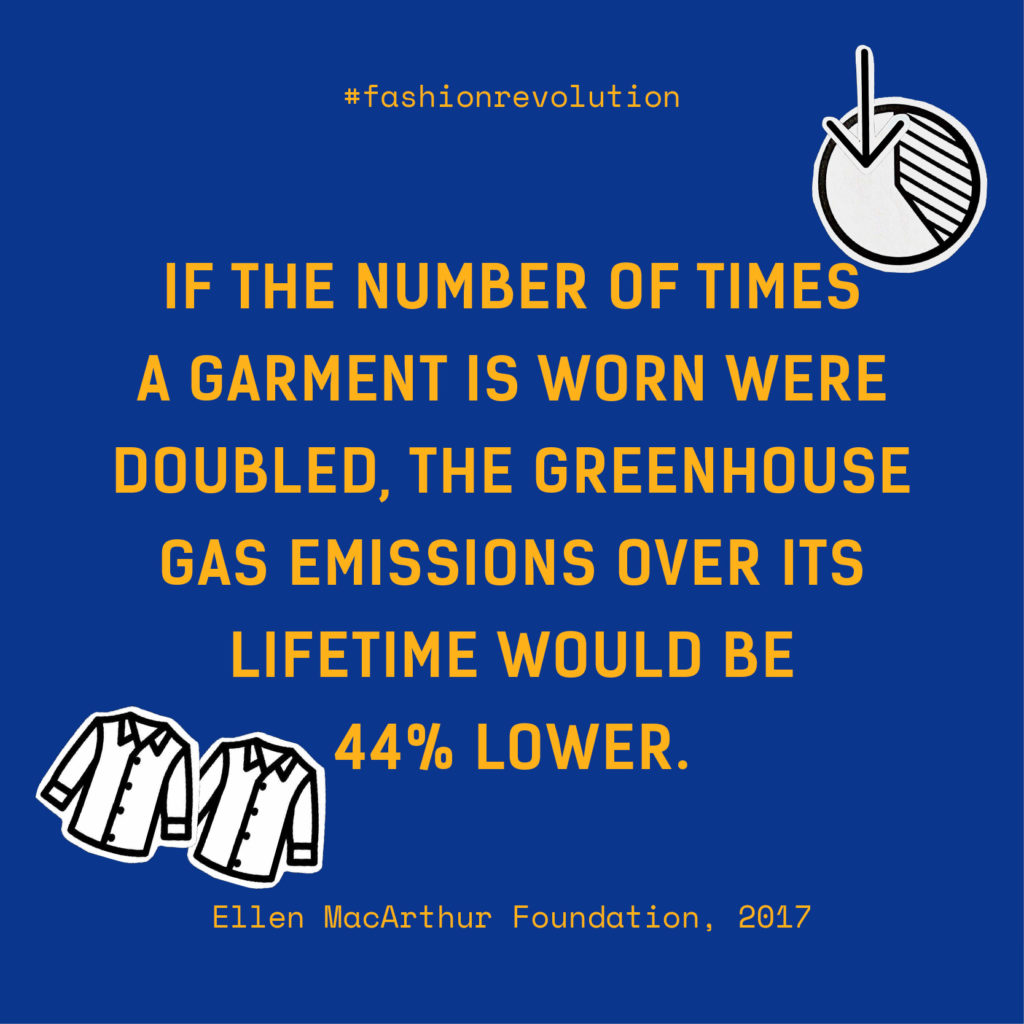

A t-shirt that will often, if bought from mainstream retailers, have been made for poverty wages by vulnerable people with no freedom to fight for more. Perhaps clothes have never been as political as they are now, in the era of throwaway fashion – when our choice of clothes is no longer just about expressing ourselves, but potentially oppressing others.

“Fashion is an area where people can really drive meaningful social and environmental change through their choices,” says Rachel England, author of new book Everyday Activism: How to Change the World in Five Minutes, One Hour or a Day. “It’s no secret that ‘fast fashion’ – cheap, mass-produced low-quality items – are bad news, so the most positive action you can take here is to simply avoid it. Instead, choose well-made durable items from brands that put sustainability front and centre of their operations.”

That’s the crux of my own book, How To Break Up With Fast Fashion, and the main message of many a slow fashion Instagram feed: buy better and buy less. But, we might ask, what then? How do we turn inactivity into a force for positive change?

If the first step is to scale back our own consumption and make the most of what we have, the second is to look beyond our own wardrobes and see the bigger picture. Fashion reflects and intersects with so many stratas of social injustice – racism, colonialism, sexism, ableism, fatphobia, you name it – and by tugging at one thread, they all begin to unravel.

This 19-25 April will be the eighth annual Fashion Revolution Week, marking the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse which killed 1,138 people in Bangladesh in 2013. Often regarded as the industry’s darkest day, the Rana Plaza disaster was a catalyst for action, inspiring the formation of global campaign group Fashion Revolution. Yet it was no solitary tragedy, and certainly not the last.

At the start of the pandemic, global fashion brands cancelled an estimated $40 billion worth of orders with garment factories, leaving millions of workers unemployed and destitute. As a response, the #PayUp campaign was launched by US not-for-profit Remake, and a year later more than $22 billion has been coughed up by those brands – proof that ‘clicktivism’ really can achieve real-world change.

But only if there’s a clear purpose behind the posts. Following fashion activists such as @AjaBarber, @VenetiaLaManna and @aditimayer is a great place to start – but as activist Mikaela Loach, co-host of The Yikes Podcast, has summed it up: “Social media activism isn’t all that activism is. I do think it can be a real, important, accessible form of activism [but] the folks that you follow, the ones whose names you know, the folks who do public facing work: they aren’t doing the ‘best’ or ‘most important’ work. They’re just doing one type. The majority of organising – which drives real change – happens behind the scenes.”

Now the world’s largest fashion activist movement, Fashion Revolution is organising millions of people across the world to do that work. Ruth MacGilp, the organisation’s Communications and Content Manager, tells me: “This could mean anything from direct action for the people that make our clothes, creating increased awareness for citizens through social media, holding brands accountable for their lack of transparency or taking to the streets and demanding reform from policymakers.”

Crucially, Fashion Revolution’s activism is noisy. It’s vocal. It hinges on the proactive rather than the passive – asking questions, signing petitions, educating others, lobbying decision-makers – and gives greater weight to what we do than what we buy or wear. One of the tenets of Fashion Revolution Week every year is demanding greater transparency from brands – either by emailing them, leaving online product reviews, or via social media, using the hashtags #WhoMadeMyClothes, #WhoMadeMyFabric and #WhatsInMyClothes.

But surely, some might ask, the idea of fashion activism is an oxymoron? Shouldn’t a proper activist eschew fickle, wasteful fashion in favour of life in a utilitarian boiler suit?

“Despite all of the fashion industry’s problems, we are still a pro-fashion movement,” insists MacGilp. “We love the creativity, culture and craft of fashion and we believe in the power of fashion to do good, so we stand for a better system, not a boycott.” In fact, she argues, we can change more from within the industry than by judging it from the outside. “It’s about coming together to shake up the system, not simply refusing to engage with it.”

This year’s Fashion Revolution Week will also see a huge programme of Open Studio events, where designers and fashion pioneers run workshops on everything from upcycled couture to transforming an old t-shirt. As co-founder Orsola de Castro reminds us with her new book Loved Clothes Last, ‘the joy of rewearing and repairing your clothes can be a revolutionary act.’

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to fashion activism – rather it’s a patchwork effort, with everyone working hard on their own personal square. For some, it will be spreading the word among their friends and families. For others, it’ll be supporting movements like #PayUp, or passing the mic by using their platforms to amplify other people’s voices. For others still it might be emailing brands to push for size inclusivity, or canvassing for a politician with climate change policy at the heart of their manifesto.

And sure, for those who can afford it, activism can be about money – both donating it, and choosing to spend it with purpose. If we’re going to shop, it’s shopping with social enterprise brands like Birdsong, whose beautiful tees deliver far more than a sassy slogan. But there are no entry criteria and no minimum spend requirements. We can’t buy our way to a sustainable future.

“Ultimately, the best way to use fashion as a tool of social and political change is to take action in the ways that make sense for you and your community,” says Ruth, “whether you’re a student, journalist, influencer, designer, retailer, educator, producer, or just a citizen who loves fashion but hates what it does to the world.”

It’s a motto that would look pretty good on a t-shirt. But it looks even better in action.

- Get to know Birdsong – the London-based brand who are as vocal as they are transparent

- Discover Gung Ho London whose garments focus on environmental issues with profits going to charities that focus on those causes

- Looking for a new bag? Check out Been London who use upcycled materials

- Shop new-to-site brand Jenerous, whose womenswear and childrenswear empowers women & those from low socio-economic backgrounds